Diane Wolfthal, David and Caroline Minter Professor of the Humanities in the Department of Art History, has been working with the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston on their recent acquisition of a medieval Jewish prayer book.

The Museum of Fine Arts recently acquired a fascinating maḥzor, that is, a prayer book that follows the annual cycle of Jewish holidays, and contains the additions, especially piyyutim, or liturgical poems, for special Sabbaths and festivals. Large, lavishly decorated mahzorim flourished from the mid-thirteenth to the mid-fourteenth century in southern Germany. They would have been brought to synagogue when needed, and used primarily by the ḥazzan, or prayer leader. Numerous studies have been published on mahzorim, but the example in Houston is virtually unknown, in large part because it remained in private collections before coming to Houston.

Much like contemporary Christian choir books, Rhenish maḥzorim were very large codices, usually made in pairs, each spanning half the year. One volume, today called the summer mahzor, is devoted to the special Sabbaths before Passover, to Passover, and to Shavuot, and the other, termed the winter mahzor, is devoted to the remaining major holidays. Judging by its contents, the Houston example is a summer mahzor. Its companion volume has never been identified and may be lost.

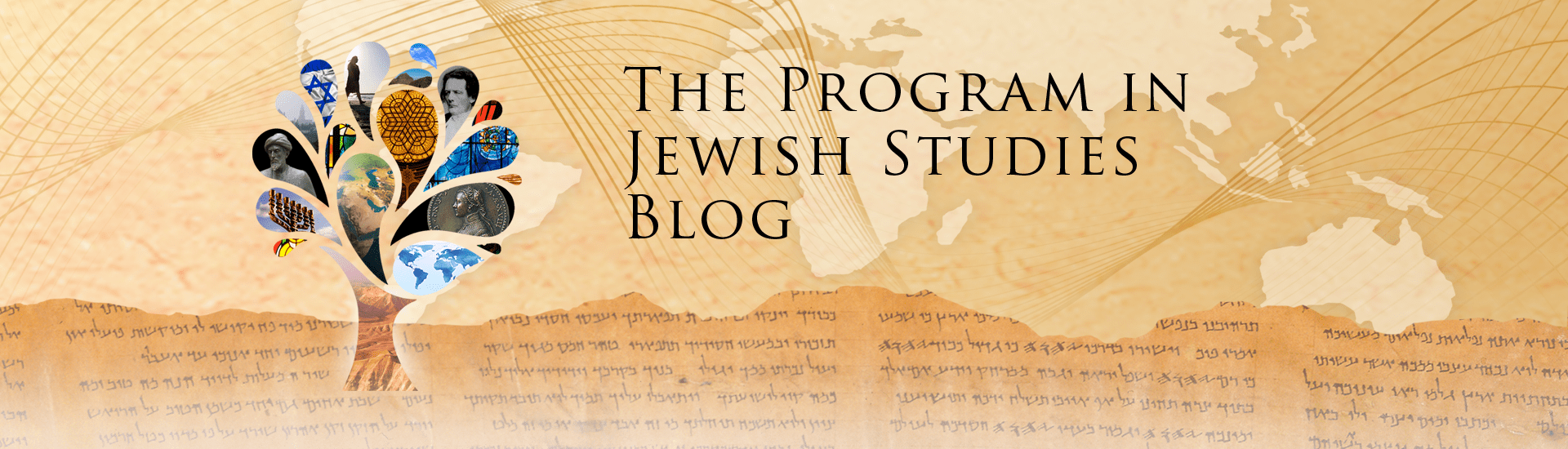

The maḥzor has suffered greatly. Many folios show the ill effects of dampness, and the first and last folios are missing, probably due to normal wear and tear. But elsewhere numerous signs of intentional damage document the manuscript’s tortuous history: parchment cut out from the lower margin, word panels and marginal decoration removed, and razor slashes. Later marginal additions are also visible. A child seems to have practiced writing letters in the blank upper border, a single letter here; the word zachor, meaning remember, here; and the Hebrew word for horse (סוּס) beside a drawing of a horse. In addition, two marginal notes give instructions to the congregation, and later owners, including Samuel David Luzzatto, the renowned poet, scholar, and member of the Wissenschaft des Judentums movement, inscribed other marginal jottings.

On a number of folios a large part of the lower border has been excised, which Tina Tan, the museum’s conservator, has suggested stems from the desire to harvest blank parchment to form a new, smaller manuscript. Some images have been cut out of the Houston mahzor, probably in the nineteenth century when owners sometimes presented attractive word panels or illuminations as gifts. Parchment may also have been harvested for tefillin, the black leather boxes that contain texts from Exodus and Deuteronomy, written on parchment.

On several pages censors crossed out words or phrases. Censors were generally Jews who had converted to Christianity, who could read Hebrew and were familiar with the texts that crossed their desks. Active in Italy especially from around 1550 through the beginning of the seventeenth century. their goal was to insure that Jewish texts were free of any derogatory references to Christianity.

The most magnificent, complex, and original illumination in the manuscript is a rare example of a brunaille illumination, that is, a monochrome composition in shades of brown. It is produced in the spare-ground technique, with the forms taking on the color of the bare parchment. It consists of a large rectangle that frames an oval, which, in turn, contains a hexagram whose lines extend to form substantial leaves, which curl back on themselves. The word “ori,” or “my light,” fills the central square. This word begins Psalm 27, which is read in the evening of the seventh night of Passover, “The Lord is my light and my salvation.” It is God who is “my light,” and so these letters are set apart for special adornment. Fantastic winged bipeds, some partially clothed, and one quadruped occupy the triangular spaces surrounding the word “ori” as well as the corners of the large rectangle. Flowers inhabit the triangular spaces just beyond the central diamond.

Originally there were at least two figural panels; both survive only in a severely fragmented state. Animal forms or expressive heads sprout from some individual words. A few are extraordinarily expressive. The Song of Songs appears twice, and in each case several of the words are divided, leaving an empty space in the middle. In the second example, the word “shinayikh,” or “teeth” is separated, leaving room for a lively figure who pulls the two parts of the word together with a rope.

Some of the images make clear that Jews and Christians shared cultural ideas. Monkeys beat drums in a catchword in the manuscript and in later Christian books, and a man pulls missing words into place with a rope in an earlier English Book of Hours. All these examples are playful, far from the fraught category of religious ideas. Jews felt comfortable sharing such motifs.

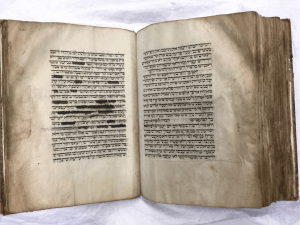

One folio, however, unmistakably expresses ideas that stem from the Jewish medieval experience. It is no coincidence that growing out of the word “aluf,” which means “champion” or “prince,” is a profile head that is marked as a Jew by his pointed hat. In a move typical of subjugated people, this image looks like a meaningless doodle that is easy to overlook, but it allowed medieval Jews to imagine that they were champions or princes, rather a landless, powerless, oppressed minority.

Innumerable questions about the Houston Mahzor remain. But their answers must await further research.

I’m so glad to read this. I saw the manuscript at the museum, and this explanation beautifully “illuminates” the experience.